As 2026 began, the cybersecurity market revealed a clear direction.

- ServiceNow acquired Armis in an all-cash $7.75B deal.

- CrowdStrike acquired SGNL ($740M) and Seraphic (≈$400M) in succession.

- Palo Alto Networks was reported to be evaluating the acquisition of Koi Security (not confirmed).

- Cisco was rumored to pursue Axonius, a claim Axonius later denied.

Some deals closed. Some were explored. One was denied. The signal, however, is consistent. The market is no longer buying isolated capabilities.

It is building a structure that can govern reality, a Security OS.

What These Companies Are Actually Buying and Why the Old Product Frame No Longer Works

On the surface, these acquisitions look familiar: asset management, OT security, browser protection, identity, EDR adjacencies. Structurally, they are buying something else. They are buying answers to a shared set of questions:

- What actually exists in the organization right now?

- What is running?

- What actions are happening, and in what context?

SIEM, XDR, automation, and compliance all sit downstream of these questions. That is why these transactions are not priced on feature value. They are priced on the potential to evolve into an operating system. At this point, the traditional product frame collapses.

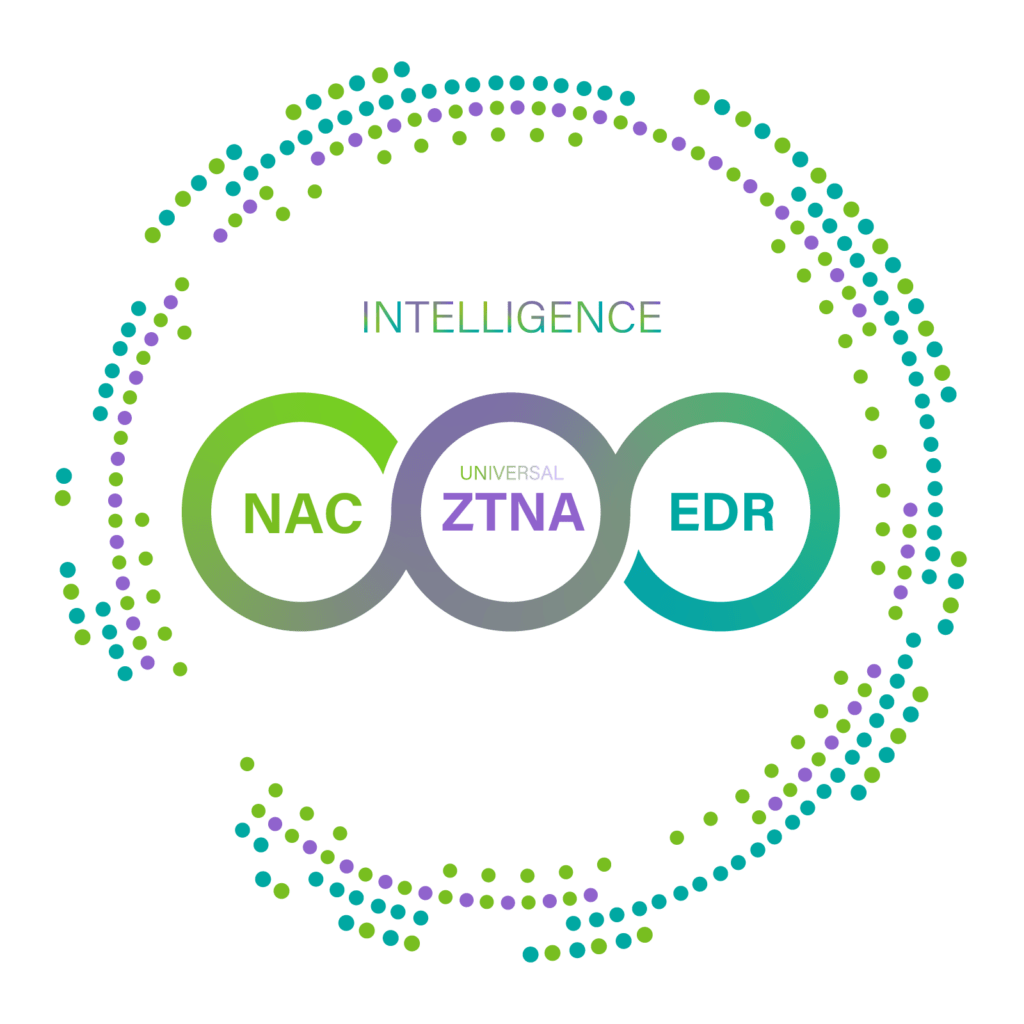

The question is no longer NAC, ZTNA, NGFW, EPP, EDR, or SIEM as categories. The market is asking how these capabilities can be assembled into a single operating system, a Security OS, with clearly defined roles and responsibilities.

The center of gravity is not detection. It is control over enforceable reality.

Is the Security OS Enough? What Is Missing?

An OS reduces complexity. At the same time, it creates a single point of failure. Is it reasonable to centralize assets, execution, response, and compliance into a single vendor OS?

That question leads to a deeper one: What reality do these Security OS models consistently overlook? Most Security OS approaches observe processes and behavior, track SaaS actions, correlate identity to execution, and analyze runtime and asset state. Yet they remain weak against one question:

Should this device be allowed to exist on the network right now?

This question is not asked after logs. Not after detection. It exists only at the moment of connection.

The Minimum Structure Required for a Security OS and Why

Reality separates into three layers.

| Reality | Meaning | Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Access Reality | Is it allowed to exist? | NAC |

| Path Reality | Where can it go? | ZTNA (NAC-anchored) |

| State Reality | Is it safe right now? | Beyond EDR |

Remove any one layer, and the OS becomes structurally incomplete. That is why NAC, NAC-anchored ZTNA, and a Beyond EDR endpoint layer are not a bundle, but a minimum requirement. Each layer operates on a different time axis and responsibility.

- Access reality determines the legitimacy of existence itself, before login and before application access, independent of accounts or agents, including exceptions. Without this decision, every downstream control runs on assumption.

- Path reality is where ZTNA matters, but ZTNA without NAC only controls routes, not reality. When NAC proves legitimate entry and ZTNA limits movement, policy becomes enforceable.

- ZTNA without NAC is a tunnel.

- NAC-anchored ZTNA is network policy at OS level.

- State reality cannot be explained by EDR alone. To know whether a device remains safe right now, the following must operate together:

- Antivirus

- Anti-ransomware

- Device Control (e.g., USB peripherals)

- EDR behavioral telemetry

Other combinations exist. But no technology yet replaces enforcement at the moment of network presence with the same scope and accountability.

Why Vendor-Native NAC Hits Structural Limits

The access layer already exists inside major portfolios:

- Cisco: ISE

- HP Aruba: ClearPass

- Fortinet: FortiNAC

The issue is not missing capability. It is structural dependency. These NAC platforms assume tight coupling to their own switches, wireless controllers, and network OS. In environments with heterogeneous vendors, legacy infrastructure, and mixed operational realities, they struggle to consistently enforce and explain access reality at OS scale. The limitation is architectural, not technical.

Does This Structure Work in Practice and What Is NAC’s Role in the OS Era?

Whether this model works in reality is already observable. Genians recorded over 35% customer growth in the Americas in 2025, with continued year-over-year expansion in the Middle East. This reflects more than short-term momentum. It reflects the extension of experience, built over two decades of operating NAC in high-density, regulation-heavy environments, into new regions.

That expansion is possible because NAC is treated not as a device that disrupts the network, but as a structure that observes reality and accumulates evidence. Genians’ NAC does not intercept traffic inline or force changes to existing switch or VLAN designs.

- State observed and recorded at the moment of connection

- Enforcement expanded only when necessary, step by step

This non-intrusive design preserves network stability while still answering a critical question:

Who connected, in what state, and when?

This clarifies NAC’s role. NAC does not replace the OS. Instead, it prevents the OS from misinterpreting reality. The competition ahead is not between operating systems, but between operating systems combined with a Reality Control Plane. That reality, particularly at the moment of connection, remains only partially owned.